visual essay exploring infrastructures of AI

this work has been presented at

- the Connective (t)Issues Workshop, with Data & Society

- and The Politics of AI: Governance, Resistance, Alternatives with Sustainable AI Futures (Goldsmith University)

Big Tech’s resource-intensive drive for AI development follows a broader pattern seen in digital infrastructures worldwide. AI hubs often perpetuate uneven distribution of benefits and burdens, amplifying socioeconomic and ecological tensions in the places where they take root. There is a variety of grassroots and non-profit initiatives which strive to make AI more accessible, however, corporate powerhouses remain positioned to hoard compute and shape technological priorities in line with market-based goals.

In many regions in the Global South, residents must rely on tangled, improvised electrical connections because local electric grids suffer from frequent outages, lack of maintenance, and overloaded capacity due to infrastructural neglect, corruption, and underinvestment. In many cases, residents are forced to rely on corrupt, overpriced, and abusive informal grid operators who exploit the lack of formal infrastructure. These operators often charge exorbitant fees for inconsistent and unsafe power access, creating a cycle of dependence that deepens socioeconomic inequalities.

These local grids, though vital for everyday survival, underscore a stark contrast between communities searching for basic utilities and the rhetoric of progress that surrounds Big Tech’s data-driven expansion. While corporations invest in stable, resource-intensive systems to power their AI initiatives, local populations struggle for basic access to electricity. This imbalance reflects broader systemic neglect of infrastructure that prioritizes private, profit-driven interests over public welfare, particularly in underprivileged areas.

At the same time, decentralized movements inspired by decolonial, feminist, and queer methodologies offer alternative narratives, rethinking who benefits from these systems and why they are built the way they are. By placing AI’s expansion within a larger ecosystem of social and physical infrastructures, this research asks how we might collectively envision more just forms of technological governance, resource distribution, and design.

By comparing informal grids in the Global South to the concentrated data infrastructure of the North, the essay explores:

- The dominance of Big Tech in shaping AI development and the resulting consequences for communities in the Global South.

- The impact of data centers on electricity and water consumption, contrasted with the rising costs and scarcity of electricity for local populations.

- The prevailing frameworks of progress employed in current AI development.

- Governance of AI, including what it means to tap into, create, and participate in AI systems with inaccessible, centralized, and non-distributed resources.

- Decolonial, feminist, and queer approaches to creating and building AI infrastructures.

The first set of images traces the chaotic tangle of electric cables found in the Burj el-Barajneh refugee camp in Beirut. These hazardous, low-hanging wires pose a constant threat to residents' lives, having caused numerous deaths and injuries over the years. This dangerous and improvised network starkly contrasts with the intricate precision of wiring on AI chips and the meticulously controlled organization within data centers. This makeshift wiring is a testament to infrastructural neglect and a symbol of the broader inequalities embedded in technological systems and resource distribution.

AI development relies on hyper-controlled, optimized environments to process vast amounts of data, while millions of people live under precarious and life-threatening electrical setups. This contrast underscores the uneven global allocation of resources and expertise, where advancements in one domain thrive at the expense of neglect in others. It also raises critical questions about priorities in technological development: Who gets to benefit from innovation, and at what cost to others?

A follow-up to this work will include additional tracings of electric cables from other neighborhoods in the Global South, printing the base image on thick paper and using a needle and thread to physically recreate the traced lines, adding a tactile and layered dimension to the piece before scanning it again for further exploration.

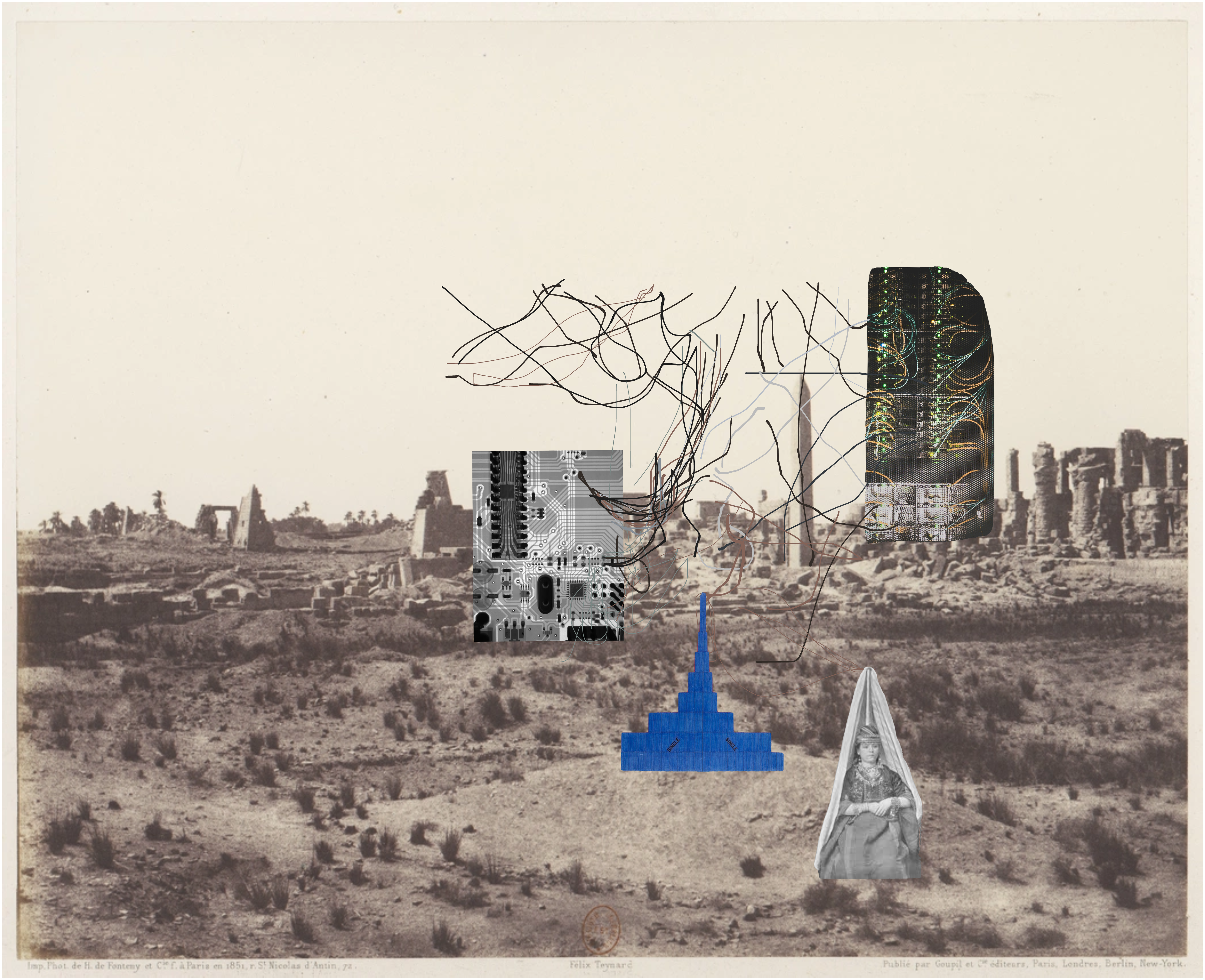

The second set of images explores AI’s reliance on hidden labor, often invisible and undervalued work historically performed by women and, more recently, by people from the Global South (Toupin, 2023). These images also draw inspiration from utopian and dystopian cityscapes, referencing 20th-century urban planning schemes like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City, which sought to reimagine the future needs of urban life.

However, such futuristic visions, whether in architecture or AI, often obscure the realities of labor and power dynamics that sustain them. Just as Broadacre City envisioned an idealized, decentralized society while glossing over the structural inequalities of the era, AI’s development leans heavily on exploitative systems of hidden labor. The invisible workforce powering AI, content moderators, data labelers, maintenance workers, factory workers, is rarely acknowledged in the narratives of technological progress.

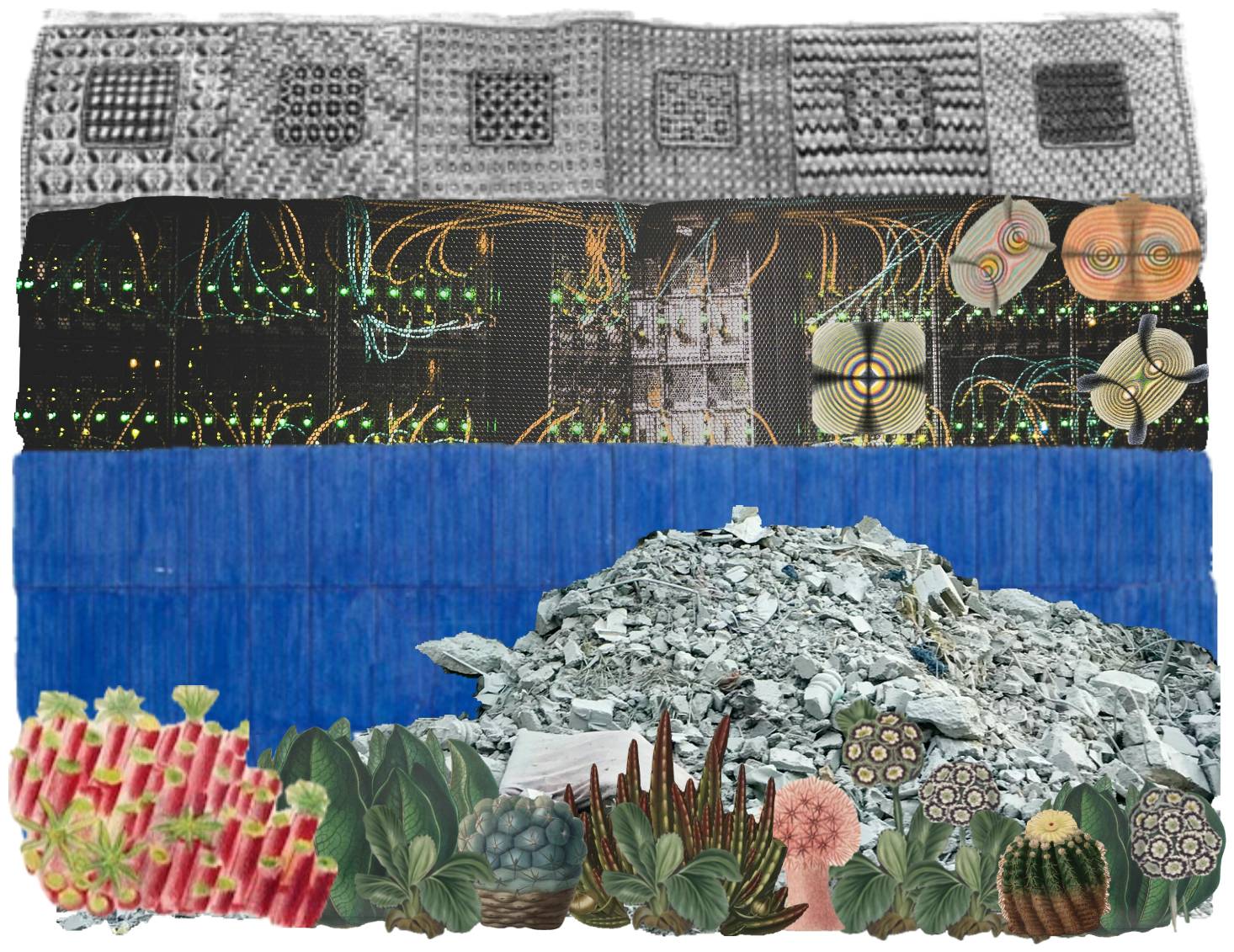

The third set of images includes elements of destruction, such as rubble from conflict zones, to explore the intertwined relationship between technology, AI, and conflict. These elements reflect the direct impact of technology on conflicts and the broader question of progress: What does progress mean if it continues to normalize destruction and perpetuate harm? Juxtaposed with these are representations of data, data servers, and plant life, symbolizing the environmental impact of technological systems and raising questions about alternative pathways forward. How might we learn from other forms of intelligence—human and non-human—and transform our societies to live more equitably with one another and the natural world?

By bringing visual contrasts into focus, the images challenge the narrative of progress that often accompanies AI and digital infrastructures. It asks us to consider how systems designed for precision and efficiency in one context might coexist with disorder and peril in another. The entanglement of wires in Burj el-Barajneh becomes a metaphor for the tangled responsibilities and inequalities that underpin global technological advancements.

References

—Toupin, Sophie. “Shaping feminist artificial intelligence.” New Media & Society 26, no. 1 (2024): 580-595.— Delacroix, Sylvie. “Sustainable Data Rivers? Rebalancing the Data Ecosystem That Underlies Generative AI.” Critical AI 2, no. 1 (2024).

— “AI Decolonial Manyfesto.” manyfesto.ai — “Better Images of AI.” betterimagesofai.org

— Elmenshawy, Mohamed. “Photo Essay: Life as a Palestinian Refugee in Lebanon.“ Middle East Monitor, n.d., https://www.everand.com/article/414129288/Photo-Essay-Life-As-A-Palestinian-Refugee-In-Lebanon.